Overview

Analogy to established networking systems

To start on some (hopefully) common ground, let's begin with an analogy to Open Systems Initiative (OSI) networking layers in this table. For a complete description of the OSI layers see http://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-X.200-199407-I/en.

| OSI Layer | Goby-Acomms library component | API class(es) | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Application | N/A | gobyd | |

| Presentation | DCCL | dccl::Codec | |

| Session | No sessions | ||

| Transport | queue | goby::acomms::QueueManager | queue_simple.cpp chat.cpp |

| Network | Does not yet exist. | ||

| Data Link | driver | subclasses of goby::acomms::ModemDriverBase, e.g. goby::acomms::MMDriver | driver_simple.cpp chat.cpp |

| amac | goby::acomms::MACManager | amac_simple.cpp chat.cpp | |

| Physical | Not part of Goby | Modem Firmware, e.g. WHOI Micro-Modem Firmware (NMEA 0183 on RS-232) (see Interface Guide) |

Acoustic Communications are slow

Do not take the OSI mapping too literally; some things we are doing here for acoustic communications (hereafter, acomms) are unconventional from the approach of networking on electromagnetic carriers (hereafter, EM networking). The difference is a vast spread in the expected throughput of a standard internet hardware carrier and acoustic communications. For example, an optical fiber can put through greater than 10 Tbps over greater than 100 km, whereas the WHOI acoustic Micro-Modem can (at best) do 5000 bps over several km. This is a difference of thirteen orders of magnitude for the bit-rate distance product!

Efficiency to make messages small is good

Extremely low throughput means that essentially every efficiency in bit packing messages to the smallest size possible is desirable. The traditional approach of layering (e.g. TCP/IP) creates inefficiencies as each layer wraps the message of the higher layer with its own header. See RFC3439 section 3 ("Layering Considered Harmful") for an interesting discussion of this issue http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3439#page-7. Thus, the "layers" of goby-acomms are more tightly interrelated than TCP/IP, for example. Higher layers depend on lower layers to carry out functions such as error checking and do not replicate this functionality.

Total throughput unrealistic: prioritize data

The second major difference stemming from this bandwidth constraint is that total throughput is often an unrealistic goal. The quality of the acoustic channel varies widely from place to place, and even from hour to hour as changes in the sea affect propagation of sound. This means that it is also difficult to predict what one's throughput will be at any given time.

These two considerations manifest themselves in the goby-acomms design as a priority based queuing system for the transport layer. Messages are placed in different queues based on their priority (which is determined by the designer of the message). This means that the channel is always utilized (low priority data are sent when the channel quality is high) but important messages are not swamped by low priority data. In contrast, TCP/IP considers all packets equally. Packets made from a spam email are given the same consideration as a high priority email from the President. This is a trade-off in efficiency versus simplicity that makes sense for EM networking, but does not for acoustic communications.

Despite all this, simplicity is good

The "law of diminishing returns" means that at some point, if we try to optimize excessively, we will end up making the system more complex without substantial gain. Thus, goby-acomms makes some concessions for the sake of simplicity:

- Numerical message fields are bounded by powers of 10, rather than 2. Humans deal much better with decimal than binary.

- User data packetizing (and subsequent unpacketizing) is not done. This is a key component of TCP/IP, but with the number of dropped packets one can expect with acomms, at the moment this does not seem like a good idea. The user is expected to provide data that is smaller or equal to the packet size of the physical layer (e.g. 32 - 256 bytes for the WHOI Micro-Modem).

Component model

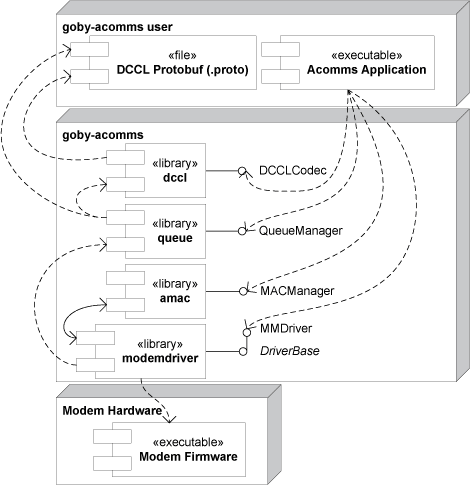

A relatively simple component model for the goby-acomms library showing the interface classes:

dccl: Encoding and decoding

The Dynamic Compact Control Language (DCCL) provides a structure for defining messages to be sent through an acoustic modem. The messages are configured in Google Protocol Buffers and are intended to be easily reconfigurable, unlike the original CCL framework used in the REMUS vehicles and others (for information on CCL, see http://acomms.whoi.edu/ccl/.

Unlike the encoder / decoder provided with Google Protocol Buffers, each field (which could be a primitive type like double, int32, string or an user-defined embedded message like CTDMessage) of a DCCL message can be encoded using a DCCL built-in or user-defined encoder. This allows the codecs to be matched to the data's physical origins and thus make the most of the limited throughput available by making very small encoded messages.

DCCL is now a standalone library that can be used with or without Goby. See http://libdccl.org for detailed documentation.

queue: Priority based message queuing

The goby-acomms queuing (queue) component interacts with both the application level process and the modem driver process that talks directly to the modem.

On the application side, queue provides the ability for the application level process to push DCCL messages to various queues and receive messages from a remote sender that correspond to messages in the same queue (e.g. you have a queue for STATUS_MESSAGE that you can push messages to you and also receive other STATUS_MESSAGEs on). The push feature is called by the application level process and received messages are signaled to all previous bound slots (see signal_slot).

On the driver side, queue provides the modem driver with data upon request. It chooses the data to send based on dynamic priorities (and several other configuration parameters). It will also pack as many messages from the user into a single frame from the modem as possible using the DCCLCodec's repeated encoding functionality. Note, however, that queue will not split a user's data into frames (like TCP/IP). If this functionality is desired, it must be provided at the application layer. Acoustic communications are too unpredictable to reliably stitch together frames.

Detailed documentation for queue

modemdriver: Modem driver

The goby-acomms Modem driver component (modemdriver) of the Goby-Acomms library provides an interface from the rest of goby-acomms to the acoustic modem firmware. While currently the only driver publicly available is for the WHOI Micro-Modem (and for an example toy modem "ABCDriver"), this component is written in such a way that drivers for any acoustic modem that interfaces over a serial or TCP connection and can provide (or provide abstractions for) sending data directly to another modem on the link should be able to be written. Contributions of a modem driver for another acoustic modem are highly welcome.

Detailed documentation for modemdriver

amac: Medium Access Control (MAC)

The goby-acomms MAC component (amac) handles access to the shared medium, in our case the acoustic channel. We assume that we have a single (frequency) band for transmission so that if vehicles transmit simultaneously, collisions will occur between messaging. Therefore, we use time division multiple access (TDMA) schemes, or "slotting". Networks with multiple frequency bands will have to employ a different MAC scheme or augment amac for the frequency division multiple access (FDMA) scenario.

The Goby AMAC provides two basic types of TDMA:

- Decentralized: Each node initiates its own transaction at the appropriate time in the TDMA cycle. This requires reasonably well synchronized clocks (any skew must be included in the time of the slot as a guard, so skews of less than 0.1 seconds are generally acceptable.).

- Centralized (also called "polling"): For legacy support, "polling" is also provided. This is a TDMA enforced by a central computer (the "poller"). The "poller" sends a request for data from a list of nodes in sequential order. The advantage of polling is that synchronous clocks are not needed and the MAC scheme can be changed on short notice by the topside operator. Clearly this only works with modem hardware capable of third-party mediation of transmission (such as the WHOI Micro-Modem).

Detailed documentation for amac

Software concepts used in goby-acomms

Signal / Slot model for asynchronous events

The layers of goby-acomms use a signal / slot system for asynchronous events such as receipt of an acoustic message. Each signal can be connected (goby::acomms::connect()) to one or more slots, which are functions or member functions matching the signature of the signal. When the signal is emitted, the slots are called in order they were connected. To ensure synchronous behavior and thread-safety throughout goby-acomms, signals are only emitted during a call to a given component's API class do_work method (i.e. goby::acomms::ModemDriverBase::do_work(), goby::acomms::QueueManager::do_work(), goby::acomms::MACManager::do_work()).

For example, if I want to receive data from queue, I need to connect to the signal QueueManager::signal_receive. Thus, I need to define a function or class method with the same signature:

At startup, I then connect the signal to the slot:

If instead, I was using a member function such as

I would call connect (probably in the constructor for MyApplication) passing the pointer to the class:

The Boost.Signals2 library is used without modification, so for details see https://www.boost.org/doc/libs/1_58_0/doc/html/signals2.html.

Google Protocol Buffers

Google Protocol Buffers are used as a convenient way of generating data structures (basic classes with accessors, mutators). They can also be serialized efficiently, though this is not generally used within goby-acomms. Protocol buffers messages are defined in .proto files that have a C-like syntax:

The identifier "optional" means a proper MyMessage object may or may not contain that field. "required" means that a proper MyMessage always contains such a field. "repeated" means a MyMessage can contain a vector of this field (0 to n entries). The sequence number "= 1" must be unique for each field and determines the serialized format on the wire. For our purposes it is otherwise insignificant. See https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/docs/proto for full details.

The .proto file is pre-compiled into a C++ class that is loosely speaking (see https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/docs/reference/cpp-generated for precise details):

Clearly the .proto representation is more compact and amenable to easy modification. All the Protocol Buffers messages used in goby-acomms are placed in the goby::acomms::protobuf namespace for easy identification. This doxygen documentation does not understand Protocol Buffers language so you will need to look at the source code directly for the .proto (e.g. acomms_modem_message.proto).

UML models

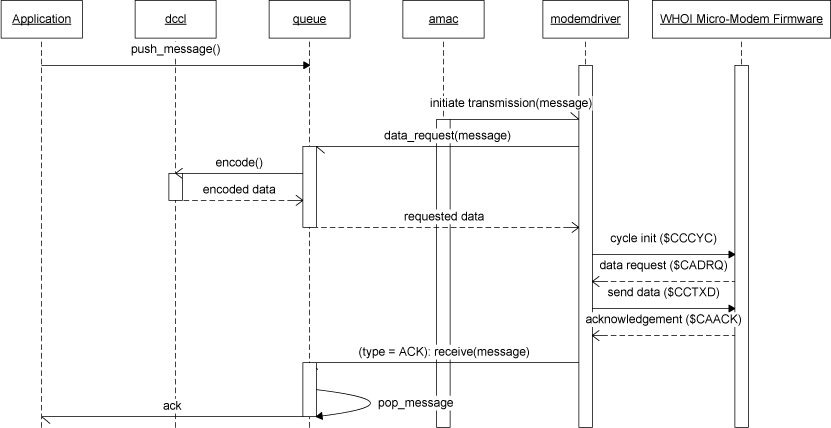

Model that gives the sequence for sending a message with goby-acomms (using the :

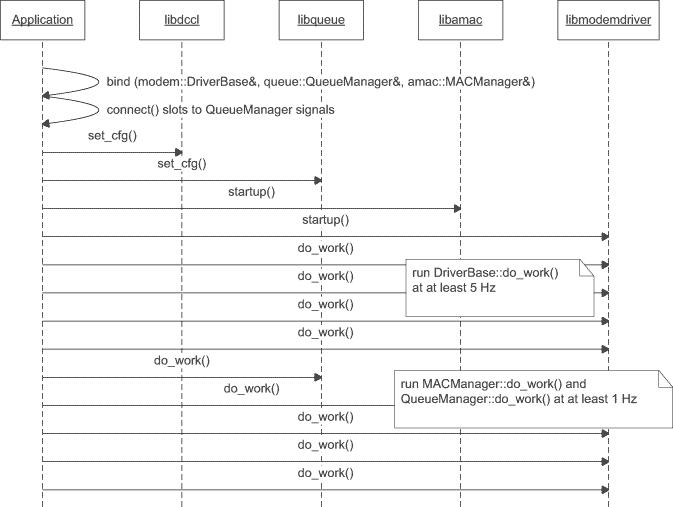

Model that shows the commands needed to start and keep goby-acomms running: